When you pick up a generic pill, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. But what if the batch you’re holding isn’t even close to the one used in the bioequivalence study? That’s not a hypothetical-it’s a real problem hiding in plain sight. For decades, regulators have approved generic drugs based on tests comparing just one batch of the generic to one batch of the brand. But research shows that batch-to-batch differences can account for 40% to 70% of the total variability in how the drug behaves in the body. That means the test you’re relying on might be measuring luck-not reliability.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

Bioequivalence is the legal standard that lets a generic drug enter the market without repeating expensive clinical trials. The idea is simple: if the generic delivers the same amount of active ingredient to your bloodstream at the same speed as the brand, it’s considered therapeutically equivalent. The test? Measure two key numbers-AUC (total drug exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration)-and check if the ratio between the generic and brand falls between 80% and 125%. That’s the rule set by the FDA in 1992 and copied worldwide. But here’s the catch: that 80-125% range was never meant to account for differences between manufacturing batches. It assumes that every batch of the brand-name drug is identical. In reality, they’re not. Even the best manufacturers see small shifts in dissolution, particle size, or coating thickness across batches. These differences don’t make the drug unsafe-but they do change how quickly it’s absorbed. And when you test a single generic batch against a single brand batch, you’re not testing the product-you’re testing two random samples.Why One Batch Isn’t Enough

A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics looked at multiple batches of the same brand-name drug. When they compared different batches to each other, the AUC and Cmax ratios often fell outside the 80-125% range. That’s right-the same drug, made by the same company, in the same factory, sometimes failed bioequivalence when tested against itself. This isn’t a flaw in manufacturing. It’s a flaw in the test. The current system treats batch variability as noise-something to be averaged out. But when batch differences make up most of the noise, you’re not averaging-you’re guessing. And when you guess, you risk approving a generic that behaves differently in real patients, or rejecting one that’s perfectly safe. Imagine two generic manufacturers. One uses a batch that happens to be very similar to the brand batch used in the study. It passes easily. Another uses a perfectly good batch that’s slightly different. It fails. The first gets approved. The second doesn’t. But both are equally effective. That’s not science. That’s roulette.

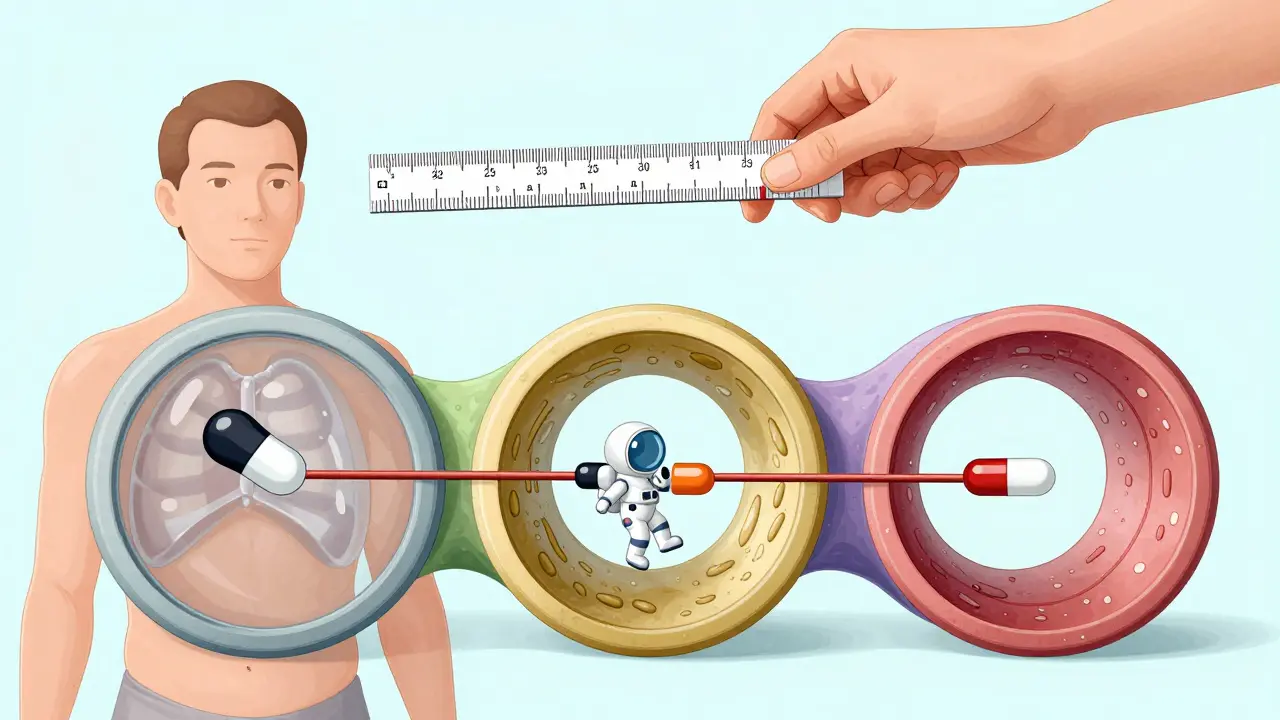

The New Approach: Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE)

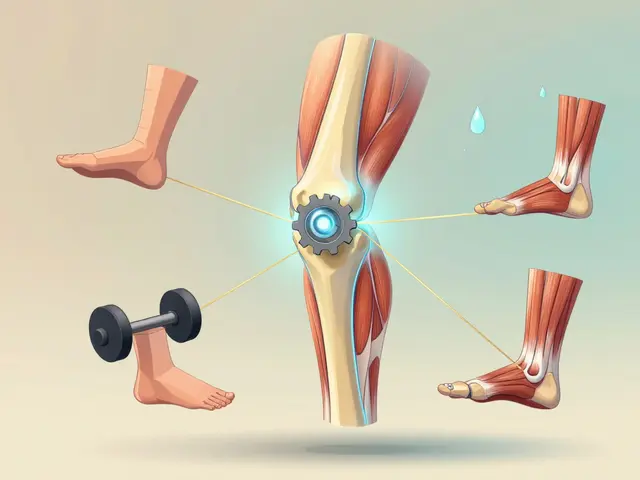

A better way exists. It’s called Between-Batch Bioequivalence, or BBE. Instead of comparing one generic batch to one brand batch, BBE compares the average of multiple generic batches to the average of multiple brand batches-and then compares that difference to how much the brand batches vary among themselves. Here’s how it works: If the brand’s batches vary by ±15% in Cmax, then the generic can vary by up to ±15% from the brand’s average and still be considered equivalent. The margin isn’t fixed at 80-125%. It’s flexible. It adapts to the product. This method doesn’t require more patients. It just requires more batches. Studies show that testing three brand batches and two generic batches boosts accuracy from about 65% to over 85%. That’s a huge jump in confidence. And it’s especially important for complex products like inhalers, nasal sprays, or topical gels-where tiny manufacturing changes can have big effects on how the drug works. The FDA already uses a version of this for budesonide nasal spray. The EMA and other regulators are starting to take notice. In 2023, the EMA’s workshop on complex generics listed “inadequate consideration of batch variability” as one of the top three challenges in generic drug approval.What’s Changing in the Rules

Regulators are waking up. In June 2023, the FDA released a draft guidance titled Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies. It’s not law yet-but it’s a clear signal. The final version is expected in mid-2024. It will likely require manufacturers of complex generics to test at least three batches of the reference product and two of the test product. The European Medicines Agency is also reviewing its guidelines. A public consultation is underway. Industry surveys show that 78% of major generic manufacturers now test multiple batches for complex products-up from just 32% in 2018. That’s not because they’re being nice. It’s because they’ve seen how often single-batch tests fail or mislead. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is working on a new guideline, Q13, focused on continuous manufacturing. Even though it’s about production methods, it’s built around the same idea: consistency across batches matters. And if you’re making drugs with consistent quality, you don’t need to rely on a single lucky batch to prove equivalence.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, this shouldn’t change how you feel about generics. Most are still safe and effective. But now you know why some generics work better than others-not because one is “better,” but because the testing system used to be broken. If you’re a pharmacist or clinician, you might notice small differences in how patients respond to different generic brands. That’s not random. It could be batch variability slipping through the cracks. Ask your supplier: “Do you test multiple batches for bioequivalence?” If they don’t know, it’s worth digging deeper. If you’re in the industry, the message is clear: stop relying on single-batch tests for complex products. Start building multi-batch data into your submissions. The regulators are coming. And the science is already there.The Bottom Line

The 80-125% rule was a good start. But it was never meant to be the final answer. Batch variability isn’t a minor detail-it’s a core part of drug performance. Ignoring it means we’re approving drugs based on coincidence, not confidence. The future of bioequivalence isn’t about tighter limits. It’s about smarter testing. More batches. Better stats. Real-world consistency. And if we get this right, we won’t just have more generics-we’ll have better ones.Why do some generic drugs seem to work differently than others?

Different batches of the same generic drug can have slight manufacturing differences that affect how quickly the drug is absorbed. If a company only tests one batch for bioequivalence, that result might not represent all future batches. Some batches may absorb faster or slower than others, leading to noticeable differences in how patients feel-even if all batches are technically approved.

Is the 80-125% bioequivalence range still valid?

Yes, but only for simple drugs with low variability. For complex products like inhalers, nasal sprays, or extended-release tablets, the 80-125% range doesn’t account for batch differences. Regulators are moving toward flexible limits based on actual batch variability, not fixed numbers. The old rule isn’t wrong-it’s outdated for many modern drugs.

How many batches should be tested for bioequivalence?

For simple oral tablets, one batch may still be acceptable. But for complex products, regulators now recommend at least three batches of the reference product and two of the test product. This gives a clearer picture of real-world consistency. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance supports this approach, and it’s expected to become standard by 2025.

Does batch variability mean generic drugs are unsafe?

No. Most generic drugs are safe and effective. The issue isn’t safety-it’s consistency. A drug might be perfectly safe but behave differently in some patients due to batch differences. That’s why we need better testing: to ensure every batch performs like the one tested, not just the lucky one.

What’s the difference between ABE and BBE?

Average Bioequivalence (ABE) compares a single test batch to a single reference batch using a fixed 80-125% range. Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE) compares the average of multiple test batches to the average of multiple reference batches, then checks if the difference is smaller than the natural variation between the reference batches. BBE is more accurate because it accounts for real-world manufacturing differences.

Are all generic drugs tested the same way?

No. Simple drugs like immediate-release tablets are still tested using single-batch ABE. But for complex products-like inhalers, injectables, or extended-release formulations-manufacturers are increasingly using multi-batch testing. Regulators are pushing for this shift, and by 2025, it will likely be required for most non-simple generics.

Can I tell if a generic drug was tested on multiple batches?

Not directly. Manufacturers aren’t required to list batch testing details on packaging. But you can ask your pharmacist or check the drug’s regulatory submission on the FDA or EMA website (if publicly available). The trend is moving toward transparency, but full disclosure isn’t standard yet.

Why hasn’t this been fixed sooner?

Because the system worked well enough for simple drugs. For decades, most generics were basic pills with little variability. But as more complex drugs-like biologics, inhalers, and modified-release formulations-became generics, the old method started to break down. The science caught up faster than the regulations. Now, regulators are playing catch-up.

12 Comments

This is why I stopped buying generics altogether

/p>They slip in different batches and you never know if you're getting the real thing or some lab experiment

Big Pharma and the FDA are in bed together and they don't care if you feel weird after taking your pills

The 80–125% bioequivalence range was always a statistical convenience, not a pharmacological truth. It’s astonishing that this outdated paradigm persists in the face of robust evidence demonstrating intra-formulation variability exceeding regulatory thresholds. The scientific community has been screaming about this for years.

/p>I’ve been a pharmacist in Mumbai for 18 years and I’ve seen patients switch between generics and swear one works better than the other

/p>At first I thought it was placebo but now I know it’s real

Some batches just hit different

Doctors don’t talk about this but we see it every day

Patients get anxious when their meds feel off and we have no way to explain why

Thank you for saying this out loud

We need more transparency

Not just for big drugs but for the little ones too

Every pill matters

My mom takes blood pressure meds and she says the blue pills make her dizzy but the white ones don’t

/p>I used to think she was being dramatic

Now I get it

It’s not about the brand

It’s about the batch

And nobody tells you that

So basically the system is rigged like a casino and we’re all just rolling dice for our meds

/p>Some days you win some days you feel like crap

And they call it medicine

I never knew this

/p>My aunt takes diabetes pills and sometimes she feels weak

I thought it was her diet

Now I think maybe it’s the batch

This makes perfect sense. The current model assumes manufacturing is perfectly consistent, which is absurd. Even the most advanced facilities have micro-variations. BBE isn’t just better-it’s inevitable. The science is settled. Now it’s just about policy catching up.

/p>Yankees think they invented medicine. We’ve been doing multi-batch testing in the UK since the 90s. Your FDA’s just playing catch-up. Again.

/p>As a regulatory affairs professional, I can confirm: the draft FDA guidance on batch-to-batch variability represents a seismic shift. The industry is already adapting. The transition from ABE to BBE for complex generics will be mandatory within 18–24 months. This isn’t theory-it’s operational reality. Transparency will increase, and patient outcomes will improve.

/p>Oh great. Now we’re going to spend millions testing 3 batches of every generic just so the FDA can feel better? Meanwhile, real drugs are still unaffordable. This is bureaucratic overkill wrapped in scientific jargon. We don’t need more testing-we need cheaper drugs. Stop over-engineering the problem.

/p>Thank you for writing this with such clarity. The gap between regulatory standards and real-world pharmacology has been widening for decades. BBE isn’t a radical idea-it’s a necessary evolution. The fact that it’s being adopted for inhalers and nasal sprays proves its validity. Let’s expand it to all non-simple formulations. Patients deserve nothing less.

/p>I cried reading this

/p>My brother died because his seizure meds didn’t work right

They said it was ‘individual variation’

But what if it wasn’t variation?

What if it was a bad batch?

And no one ever told us?

I’m so angry and so relieved someone finally said it

Thank you

For saying it out loud