Esophageal Cancer Risk: What You Need to Know About Causes, Prevention, and Medication Impact

When you think about esophageal cancer risk, the likelihood of developing cancer in the tube connecting your throat to your stomach. Also known as esophagus cancer, it doesn’t show up often—but when it does, it’s often caught too late. Most cases are linked to long-term damage from acid reflux, smoking, or heavy alcohol use. It’s not random. It’s the slow result of repeated irritation.

One of the biggest warning signs is Barrett’s esophagus, a condition where the lining of the esophagus changes due to chronic acid exposure. It’s not cancer, but it’s a known precursor. About 5% of people with long-term acid reflux develop it. If you’ve had heartburn for more than five years, especially if it’s getting worse or you’re over 50, you should talk to your doctor about screening. The good news? Catching changes early gives you a real shot at stopping cancer before it starts.

Medications play a tricky role here. Some drugs meant to help your stomach—like long-term proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for acid reflux—can mask symptoms without fixing the root cause. That’s why medication safety, how you use drugs over time to avoid unintended harm matters so much. Taking PPIs for years without monitoring isn’t harmless. It can delay diagnosis. And while these drugs reduce acid, they don’t stop the physical damage from reflux. Meanwhile, smoking and drinking don’t just add risk—they multiply it. People who do both have up to 10 times higher risk than those who don’t.

It’s not just about what you put in your mouth—it’s about what stays there. Obesity increases pressure on your stomach, pushing acid upward. Eating large meals late at night does the same. Even sleeping flat can make reflux worse. Simple changes—losing weight, eating earlier, raising the head of your bed—can cut your risk without a single pill.

There’s also a connection to how your body handles inflammation and healing. Some people have genetic factors that make their esophagus more sensitive to damage. Others develop it from long-term use of certain painkillers or even supplements that irritate the lining. You won’t find this in every article, but it shows up in real patient cases. If you’re on chronic medication for anything—blood pressure, depression, arthritis—ask your doctor if it could be contributing to esophageal irritation.

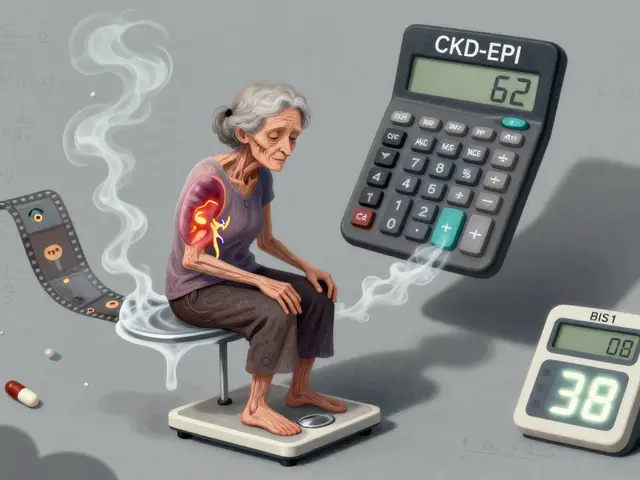

What you’ll find in the posts below aren’t scare tactics or vague advice. These are real, practical discussions from people who’ve been there: how to spot early signs, how to talk to your doctor about reflux without being brushed off, and which medications might be helping or hurting your long-term health. You’ll see how kidney disease patients need to adjust their meds to avoid further damage, how HRT can interact with other drugs, and why knowing your exact dose on a liquid label matters more than you think. It’s all connected. Your esophagus doesn’t exist in a bubble. It’s part of a system—and what you do for your stomach, your liver, your heart, even your sleep, affects it.

Chronic GERD Complications: Understanding Barrett’s Esophagus and When to Get Screened

Chronic GERD can lead to Barrett’s esophagus-a precancerous condition that increases esophageal cancer risk. Learn who should be screened, how it’s diagnosed, and what treatments actually work.