When your body’s master hormone gland starts producing too much of one hormone, everything else can go out of sync. That’s what happens with prolactinomas-a type of pituitary adenoma that overproduces prolactin. These aren’t cancerous tumors, but they can cause real, disruptive symptoms: missed periods, breast milk when you’re not pregnant, low sex drive, and even infertility. For men, it’s often erectile dysfunction, reduced body hair, or loss of muscle mass. And because the pituitary sits right behind your eyes, larger tumors can blur your vision or cause blind spots.

What Exactly Is a Pituitary Adenoma?

The pituitary gland is no bigger than a pea, but it controls hormones that regulate everything from your metabolism to your reproductive system. A pituitary adenoma is a benign growth that forms in this gland. About 1 in 10 people have one, but most never know it-they’re small and don’t make extra hormones. The ones that cause problems are called functional adenomas. Prolactinomas make up 40% to 60% of those. Other types can overproduce cortisol, growth hormone, or thyroid-stimulating hormone, each triggering its own set of symptoms.

Size matters here. Tumors under 1 centimeter are called microadenomas. These are common and often respond well to medication. Those over 1 cm are macroadenomas. They’re more likely to press on nerves, especially the optic chiasm-the spot where your optic nerves cross-and cause vision loss. About 80% of pituitary adenomas are microadenomas. The rest? Larger, trickier, and more likely to need surgery.

How Prolactinomas Disrupt Hormones

Prolactin’s job is to trigger milk production after childbirth. But when a tumor makes too much of it, your body thinks it’s pregnant-even if it’s not. In women, this shuts down estrogen production. That leads to irregular or absent periods, trouble getting pregnant, and sometimes spontaneous milk flow. Up to 95% of women with prolactinomas experience these symptoms.

Men don’t get milk, but they get hit just as hard. High prolactin lowers testosterone. That means less libido, weaker erections, fatigue, and even gynecomastia (breast tissue growth). About 80% of men with prolactinomas have sexual dysfunction. Many don’t connect the dots until they’re tested for infertility.

What makes prolactinomas tricky is that stress, certain medications (like some antidepressants or antipsychotics), and even pregnancy can raise prolactin levels too. That’s why doctors don’t just test prolactin once-they look at the level and the context. A prolactin over 150 ng/mL has a 95% chance of being a prolactinoma. Levels above 200 ng/mL almost always mean a macroadenoma.

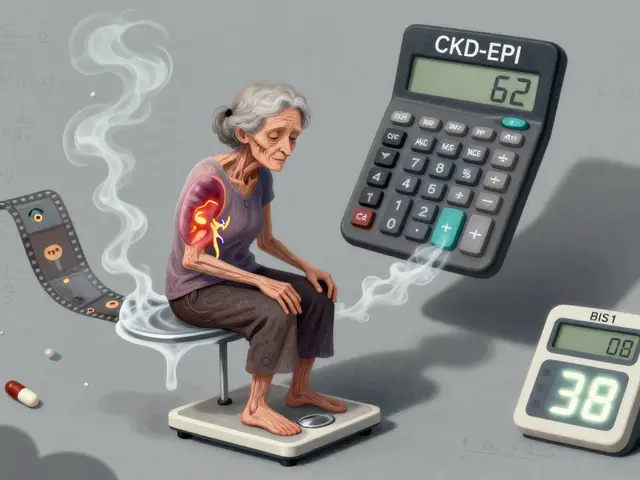

Diagnosis: Blood Tests, MRI, and Vision Checks

Diagnosing a prolactinoma isn’t guesswork. It’s a three-step process. First, a blood test checks prolactin levels. If it’s high, they’ll repeat it to rule out temporary spikes. Next, an MRI of the brain with 3mm slices is done to see the tumor’s size and location. This isn’t a regular head MRI-it’s a specialized pituitary protocol. Finally, if the tumor is over 1 cm, you’ll see an ophthalmologist for a visual field test. They’ll check if you’re missing peripheral vision, which is a red flag for pressure on the optic nerve.

Doctors also test other hormones-TSH, cortisol, testosterone, estrogen-to see if the tumor is affecting the whole gland. A tumor that’s big enough to squish the pituitary can cause hypopituitarism, where the gland stops making enough of several hormones. That’s why even if you’re being treated for prolactinoma, you need ongoing hormone checks.

First-Line Treatment: Dopamine Agonists

For most people with prolactinomas, the first treatment isn’t surgery-it’s a pill. Dopamine agonists like cabergoline and bromocriptine trick the tumor into thinking it’s getting the right signal to stop making prolactin. Cabergoline is now the gold standard. It’s taken twice a week, works better, and causes fewer side effects than bromocriptine, which requires daily dosing.

Studies show cabergoline normalizes prolactin in 80-90% of microadenomas and 70% of macroadenomas within three months. Tumor shrinkage happens in 85% of cases. One Mayo Clinic case followed a woman with a 2.4 cm tumor and prolactin levels of 5,200 ng/mL. After six months on cabergoline, her levels dropped to 18 ng/mL and the tumor shrank by 70%.

Side effects? Nausea, dizziness, and headaches are common at first. Most people adjust within a few weeks. Only about 18% stop cabergoline because of side effects-compared to 32% who quit bromocriptine. But there’s a catch: if you stop taking it, prolactin can spike back up in as little as 72 hours. That means most people need to stay on it long-term. About 70% of patients require lifelong treatment.

Surgery: When Pills Aren’t Enough

Surgery is reserved for cases where medication doesn’t work, isn’t tolerated, or the tumor is pressing on the optic nerve. The standard approach is transsphenoidal surgery-done through the nose, no scalp incision. Endoscopic techniques now make this minimally invasive, with hospital stays of just 3-5 days.

Success rates depend on size. For microadenomas, surgeons remove the tumor completely in 85-90% of cases. For macroadenomas? Only 50-60%. Invasive tumors that spread into the cavernous sinus (where big blood vessels and nerves live) are even harder to remove-only about 35% get fully cleared. That’s why recurrence is higher: 5% for microadenomas, but 25-30% for larger ones within five years.

Risks include CSF leaks (2-5%), temporary diabetes insipidus (5-10%), and pituitary apoplexy (1-2%). Diabetes insipidus means you pee a lot and get dehydrated-it’s treatable with desmopressin. Most people recover fully, but some need lifelong hormone replacement if the surgery damages the pituitary.

Radiation Therapy: A Slow but Safe Option

Radiation isn’t the first choice. It takes years to work. But it’s useful when tumors come back after surgery and meds aren’t an option. Two main types are used: Gamma Knife radiosurgery and fractionated external beam radiation.

Gamma Knife delivers one high-dose blast with pinpoint accuracy. It controls tumor growth in 95% of cases at five years and causes optic nerve damage in just 1-2% of patients. Conventional radiation, spread over 5-6 weeks, has a 5-10% risk of damaging the optic nerve. The downside? It can take 2-5 years for prolactin levels to normalize. About half of patients reach normal levels by year five, but 30-50% develop hypopituitarism within a decade.

Patients often feel frustrated by the delay. One survey found 68% still had symptoms after one year. But by year three, 85% saw improvement. Radiation is a long game, but for some, it’s the only safe option.

Long-Term Monitoring and Lifestyle

Even after prolactin normalizes and the tumor shrinks, you’re not done. You need regular checkups. Prolactin levels are checked every three months at first, then yearly if stable. MRI scans are done annually for the first few years, then every 2-3 years. If you’re on cabergoline long-term, your doctor will order an echocardiogram every two years if you’re taking more than 2 mg per week. High doses can rarely cause heart valve thickening.

Women who want to get pregnant can often stop cabergoline once pregnant, since the tumor rarely grows during pregnancy. But they need close monitoring. Men on long-term treatment should track bone density-low testosterone can lead to osteoporosis.

Most patients report major improvements. On patient forums, 78% saw symptom relief within 4-6 weeks of starting cabergoline. Surgery patients were 82% satisfied with their outcomes. But the journey isn’t always smooth. Missing a dose? Prolactin rebounds fast. Forgetting your follow-up? The tumor might grow unnoticed.

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

The field is evolving. In 2023, the FDA approved paltusotine for acromegaly-and early trials are testing it for prolactinomas. It’s an oral drug that targets different receptors than dopamine agonists, which could help people who don’t respond to cabergoline.

Researchers are also looking at gene mutations like GNAS and USP8 to predict which tumors will grow or resist treatment. In the next five years, doctors may use molecular profiles to pick the best drug for each person, boosting cure rates from 70% to 90%.

Still, 30% of macroadenomas remain stubborn. That’s why experts are exploring new ideas: dopamine-releasing stents placed directly in the pituitary, CRISPR therapies to fix faulty genes, and AI tools to guide surgery. These aren’t ready yet-but they’re coming.

When to See a Doctor

If you’re a woman with unexplained milk production, missed periods, or trouble getting pregnant-get tested. If you’re a man with low libido, fatigue, or breast tenderness, don’t assume it’s aging. Vision changes, headaches, or sudden hormone shifts? These aren’t normal. Early diagnosis means simpler treatment and better outcomes.

Pituitary adenomas aren’t rare. They’re just misunderstood. With the right testing and treatment, most people go on to live full, healthy lives. The key is knowing what to look for-and not ignoring the signs.

Can a prolactinoma go away on its own?

Rarely. Most prolactinomas don’t shrink without treatment. In a small number of cases, especially microadenomas, prolactin levels may drop slightly over time, but the tumor usually remains. Left untreated, macroadenomas can grow larger and cause permanent vision loss or hormone deficiencies. Medical treatment or surgery is almost always needed for long-term control.

Is cabergoline safe for long-term use?

Yes, for most people. Cabergoline has been used safely for over 20 years. At standard doses (under 2 mg per week), the risk of heart valve problems is very low-less than 1%. But if you’re on more than 2 mg per week for over three years, your doctor should monitor your heart with an echocardiogram every two years. The benefits of controlling the tumor far outweigh the risks for the vast majority of patients.

Can I get pregnant if I have a prolactinoma?

Yes, absolutely. Most women with prolactinomas can conceive after starting cabergoline, which restores ovulation. Many stop the medication once pregnant because the tumor rarely grows during pregnancy. But you’ll need close monitoring by an endocrinologist and obstetrician. In rare cases where the tumor is large, doctors may recommend continuing low-dose cabergoline throughout pregnancy to prevent growth.

Why do some people need surgery instead of medication?

Surgery is considered when medication doesn’t lower prolactin enough, causes intolerable side effects, or the tumor is pressing on the optic nerve and threatening vision. It’s also preferred for patients who want to avoid lifelong pills. For microadenomas, surgery has a high success rate. For larger tumors, it’s less effective, so doctors usually try medication first unless vision is at risk.

Do I need to see a specialist?

Yes. Pituitary adenomas require a team approach. Endocrinologists manage hormone levels and medication. Neurosurgeons handle surgery. Radiation oncologists plan radiotherapy. Even if you start with your primary doctor, you’ll be referred to a pituitary center-especially if you have a macroadenoma, vision problems, or need surgery. Community hospitals often refer complex cases to specialized centers for the best outcomes.

11 Comments

bro i had a prolactinoma and cabergoline was a game changer. took me 2 weeks to stop crying at commercials lmao. still take it twice a week like a boss. <3/p>

This is actually one of the most well-explained medical posts I’ve seen on Reddit. The way they broke down micro vs macro adenomas? Chef’s kiss. 🙌 I’ve been telling my cousin to get an MRI for months-she thought her fatigue was just ‘adulting’./p>

It’s fascinating how society ignores pituitary disorders as ‘women’s issues’ or ‘just aging’-when in reality, they’re neurological endocrine catastrophes masked as low libido or mood swings. The fact that men are 80% more likely to be misdiagnosed because they don’t lactate speaks volumes about medical bias. We need systemic change, not just pharmaceutical bandaids. And yes, I’ve read the Mayo Clinic case study. It’s tragic that 70% need lifelong treatment. That’s not a cure. That’s a life sentence./p>

i never knew pituitary tumors were this common... i thought only rich ppl got them. my bro had one and they said its like a stress ball in your brain. he took the pill and now he’s back to lifting weights. mad respect to the doc who figured it out./p>

Oh wow. So we’re just supposed to take a pill for the rest of our lives because Big Pharma decided dopamine agonists are ‘good enough’? Meanwhile, CRISPR is sitting on the shelf like it’s on vacation. This isn’t medicine. It’s corporate surrender wrapped in a lab coat./p>

So let me get this straight. You have a tumor the size of a pea that makes you cry at puppies, lose your manhood, and see double... and the treatment is a pill you take twice a week? And you call this healthcare? 😒/p>

I’m so glad someone wrote this. I was diagnosed last year and felt so alone. I didn’t know other men got gynecomastia from this. I thought it was just me being ‘weird.’ You’re not broken. You’re not lazy. You have a tumor. And it’s treatable. You got this 💪/p>

i started cabergoline and immediately felt like a different person. my partner said i stopped sighing all the time. also, i cried during the dog food commercial. that’s when i knew it was working. thanks for this post, it made me feel less crazy./p>

The statistical normalization of prolactin levels under cabergoline is statistically significant, yet the clinical heterogeneity of patient response remains grossly underreported in peer-reviewed literature. The assumption that 80-90% efficacy equates to therapeutic success ignores the psychosocial burden of chronic pharmacological dependency, particularly when hormonal feedback loops are permanently dysregulated. Furthermore, the omission of longitudinal neurocognitive outcomes in the cited studies constitutes a critical epistemological flaw./p>

I’ve been a neuroendocrine nurse for 15 years. Saw a guy come in with prolactin levels over 8,000. Looked like he’d been hit by a truck. Six months on cabergoline? He’s running marathons now. This isn’t just medicine-it’s magic. And yeah, it’s weird taking a pill for your brain’s hormone factory. But if it lets you hold your kid without feeling like a ghost? Worth every penny./p>

wait so if i stop taking it for a weekend i turn back into a zombie? 😭/p>